Corporate venturing exploded in the first half of 2021, but it isn’t new. It’s been around since the early 1900s, yet its purpose is often misunderstood or misdirected. Given the history, growing interest and recent evolution, it’s worthwhile rethinking the role corporate venturing has to play in generating genuine value for your organisation.

Corporate Venturing Context

Back in 1914, DuPont, the chemical manufacturer, pioneered corporate venture with an investment in General Motors. DuPont, 3M and others would go on to make various corporate venture-style investments and take on corporate venturing activities. Since then, corporate venturing has seen multiple iterations with plenty of data and examples to learn from.

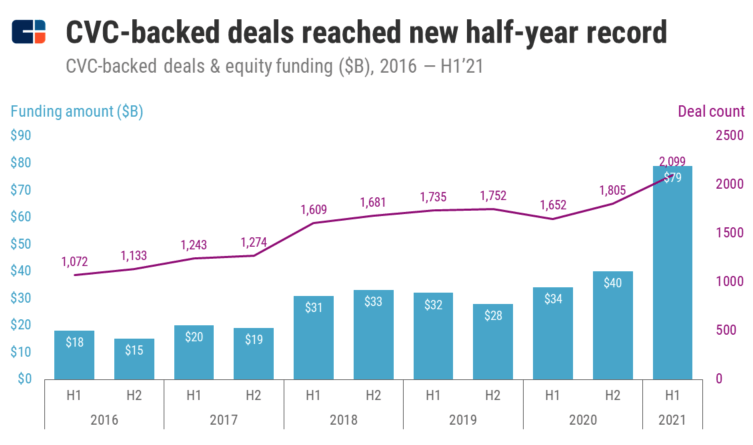

Fast forward to 2021, and there have been some notable recent developments that show a lot of activity and new entrants but domination by technology companies:

- A record spike in corporate venture funding from $40.4B in the second half of 2020 to $78.7B in the first half of 2021.

- Technology companies repeatedly dominate the list of most active corporate venturers year after year. Google, Salesforce, Coinbase and Intel dominating the charts (e.g. 188 deals in H1 2021 for 16% of total deals).

- The growing number of active corporate venture capital groups.

- The availability of venture building information (e.g. Lean Startup) leading the view that the process is known so it can be implemented in the organisation to get venture-style results.

There have also been criticisms levelled against corporates involving themselves in venturing that are worth considering:

- Lack of ability to stay the course – venture value creation in a form that will materially impact a large corporation takes time. Yet, large companies are prone to restructure and shifts in strategy over shorter horizons that make value creation difficult. This somewhat played out in the dot com bubble of 2000 when corporates withdrew sharply and more recently with COVID-19 as corporate venture activities declined (arguably most investors withdrew in both cases).

- Lack of ability to move quickly – the venture arms themselves have learned to move faster, but they can’t change the inherent speed challenges a large corporation has.

It’s these recent developments and criticism that signals it’s worthwhile rethinking corporate venturing and where it fits for a corporation. Not to mention the numerous discussions I’ve had recently with people in corporate venturing trying to get clearer on their mandate – either for themselves or so they can better explain it to their stakeholders.

More companies outside technology and pharmaceuticals are getting involved in venturing but is it the right fit? If so, what is that fit? Can you follow what is working for Google, Salesforce and Intel, or do you need something different?

Models for Corporate Venturing

Before we can answer these questions, let’s take a look at some of the models that are currently available for thinking about corporate venturing:

- Mapping Your Corporate VC Investments

- Redstone’s six types of Corporate Venture Capital

- Four Outcome-Based Approaches to Corporate Ventures

1. Mapping Your Corporate VC Investments

In 2002, Professor Henry Chesbrough asked similar questions in the Harvard Business Review, which, although triggered by slightly different events, led him to propose the following model for Mapping Your Corporate VC Investments.

Under this model, you assess how closely the venture is linked with your operational capabilities and your financial objectives. It defines four investment strategies:

- Driving Investments: investing in ventures that you work closely with on your core strategic objectives.

- Enabling Investments: investing in ventures that help with your strategic focus and operations but that you don’t require a close operational link to gain benefits.

- Emergent Investments: investing in ventures that have relevance to your operational capabilities but don’t make a meaningful impact on your current strategy.

- Passive Investments: investing in ventures that are not meaningfully connected to the corporation’s strategy or capabilities.

Chesbrough makes the argument that corporate venture investments need to be seen as an important way for a company to fuel the growth of its business. He makes an explicit case that passive investments are “arguably a misuse of shareholder’s funds.”

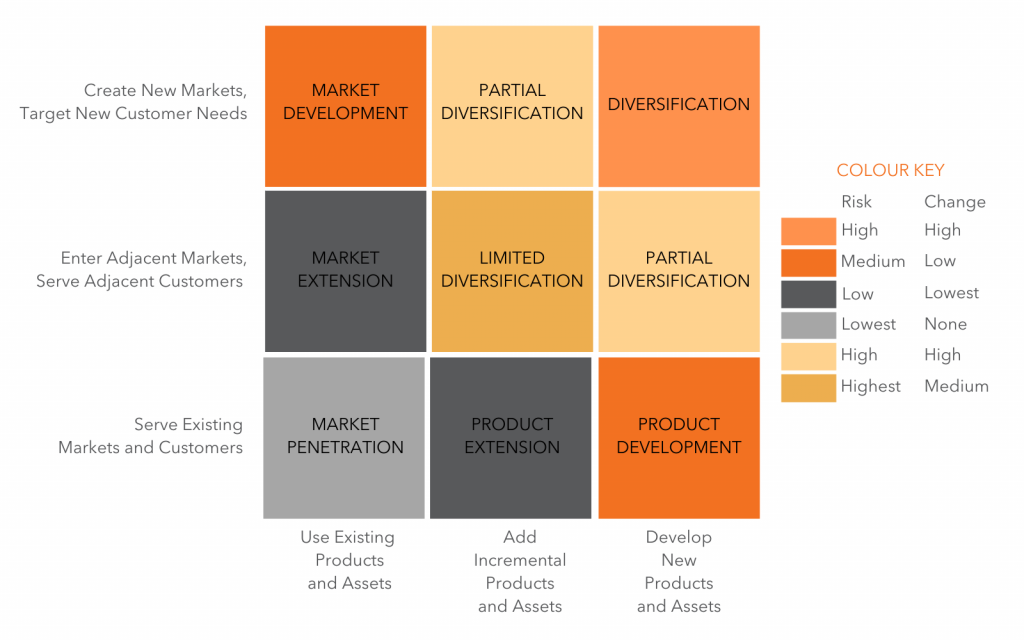

Chesbrough’s model has parallels with the time-tested Ansoff matrix that has been used for organisations to determine how to approach strategic growth, so it has strong grounding.

2. Redstone’s Six Types of Corporate Venture Capital

Redstone, a corporate venture firm that works with almost 70 corporations like VW and Munich Re, puts forward six structures for corporate venture capital:

- Single direct investments: opportunistic investments in ventures through a standard M&A process or internal funding process.

- Multiple direct investments: a slightly more structured approach to investments in ventures, often with a dedicated team or process, mostly driven by individual business units with justification made on a case-by-case basis.

- Portfolio: the allocation of capital to multiple direct investments according to a defined investment strategy.

- LP investment: corporates invest as LPs in independent venture capital funds.

- Corporate Venture Capital fund: an independent, professional fund is established that includes an independent investment committee where business units have no rights to veto decisions.

- Co-GP fund: an external venture capital partner works closely with the corporate.

The structural options available have some bearing on the models that an organisation may want (or be able) to pursue.

3. Four Outcome-Based Approaches to Corporate Ventures

For a corporate getting into venturing, there are really only four methods that make sense:

- Learn Faster

- Better Leverage

- Future Acquisition

- Encourage the Ecosystem

If you’re Google, Salesforce or Intel, then these will, on the surface, look like more general technology investments because of their reach. However, most organisations don’t have this general reach and need a more focused approach

1. Learn Faster

This method is where you make investments to gain insights, knowledge and data about key parts of your organisation’s core strategy.

This method for corporate venturing best maps to enabling or emergent approaches to corporate venturing. That is, it’s really about complementing what you are already doing and planning to do either by informing your current strategy and operations (enabling) or by informing how your current strategy might be disrupted (emergent). Your success isn’t directly linked to the venture’s success.

The key here is making the minimum investment required to participate so you can learn. The amounts required to participate are smaller than most corporates think. Yet, corporates, due to their difficulty in dealing with small numbers, tend to over-invest per investment under this strategy.

Angels are able to participate and learn from startups for under $25,000-$50,000 per investment, maybe up to $250,000, while corporations making investments in learning end up investing millions or high hundreds of thousands.

If you keep the investment cost down, the possible financial return under this method is really a secondary benefit.

2. Better Leverage

This method is where a corporate makes investments in ventures that already have a compelling case for the corporate to work with through the course of regular business (e.g. as a customer, supplier).

By making an investment, you gain leverage to influence where the venture goes, to push that direction towards what your business requires. This influence is mostly in the form of soft influence, although you can try to contract controls or requirements in.

Again, the price tag for these investments does not always need to be high to wield influence, although sometimes it can be. The financial return is again a secondary benefit but, depending on the size of the investment, it may require a little more attention than investments for learning.

This maps best to ventures that enable or help drive your strategy.

3. Future Acquisitions

This method is where a corporate makes investments in ventures that they may look to acquire. It is best suited to ventures that drive the core strategy, or that could disrupt you in the future.

With ventures that can provide a direct impact on your core strategy, your investment is about driving the investment so that it, in turn, helps drive your core strategy.

With ventures that could disrupt you, your investment is about an option for the future. You’ll be in a prime position to make an acquisition due to shareholder rights.

There are a few challenges with this approach to venturing:

- If the venture is that core to your strategy, why not acquire it now? As Uber investor Fred Wilson says, “corporations should buy companies. Investing in companies makes no sense. Don’t waste your money being a minority investor in something you don’t control. You’re a corporation! Do you want the asset? Buy it.”

- The good ventures often don’t need to do what your corporate voice wants; in fact, they’ll likely be wary of it and view you as just one of many customers or just one of many channels to market.

- If a venture does prove seriously successful, then it could be too late for you to acquire in that the valuation is higher than your organisation can (afford to) pay.

That being said, there is a primary benefit in venture investment over an acquisition: the venture remains independent, meaning it can move fast and focus. Once acquired, the venture might be impeded by your organisation – politics, more red tape, misaligned incentives.

Investing under this method means being clear on the financial outcome for your business and the venture.

4. Encourage the Ecosystem

This method is where a corporate makes investments in ventures that stimulate the corporate’s ecosystem.

This method seems to be the most successful when applied very specifically to a particular part of your organisation’s ecosystem. For example, Slack’s fund is a great example of a special purpose fund that invests in businesses building integrations with Slack.

This method maps best when it is enabling the core strategy. You aren’t concerned with one or two of the ventures in the ecosystem not working; you’re focused on the portfolio and fund itself encouraging and growing the ecosystem as a whole, which in turn directly drives your core strategy forward.

Again, the financial return becomes secondary because the primary benefit is the direct stimulation of part of your ecosystem.

Rethinking the Corporate Venturing Model

The rethink required around the corporate venturing model isn’t a wholesale rewrite, rather the next evolution of incremental refinement. The model proposed below is the result of reviewing current models and data as well as hard-won practical experience working across strategy, venturing and innovation on every side of the fence with corporates, startups, investors and product teams.

Ultimately, whether corporate venturing fits and how it fits must tie back to your overall strategy. Purely financial investments aren’t an appropriate use of shareholder capital, and a purely financially motivated venturing unit will quickly get restructured away.

With that in mind, a holistic model for determining your corporate venturing model needs to map back to your overall strategy, taking into consideration your maturity and the structures you have available for carrying out that strategy.

Determining Your Model for Corporate Venturing

If you are wondering where to go from here, then your next steps in determining the model that is right for your organisation are:

- Map venturing’s fit with the core strategy

- Select focus area(s) – pick and succeed with one method at a time

- Determine the right structure

More on Corporate Ventures:

Scott Middleton

CEO & Founder

Scott has been involved in the launch and growth of 61+ products and has published over 120 articles and videos that have been viewed over 120,000 times. Terem’s product development and strategy arm, builds and takes clients tech products to market, while the joint venture arm focuses on building tech spinouts in partnership with market leaders.

Twitter: @scottmiddleton

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/scottmiddleton