With every new corporate venture I’m involved in, the question “is this new venture big enough?” comes up and it’s always felt like we’ve answered it on the fly without taking the time to deeply understand the question and why we were asking it. We were too busy building the venture.

The tendency is to directly apply approaches from standard venture-backed startups or big business strategy because these are familiar (and easy to Google). But there are some subtle and not-so-subtle differences between internal corporate venture building and standard venture building when it comes to this question. These differences inject some nuance into the process of creating new ventures and the thinking required to determine if a venture is big enough and compelling enough to pursue.

Big business’s familiarity with macro opportunities, the appeal of long term trends, and internal drive to solve pressing business problems can pull new corporate ventures away from solving a customer problem, muddy the vision of the venture or create ventures that are really just a feature of the mothership.

This isn’t right or wrong, it’s just about being aware, so we can more effectively deal with the question: “is this new corporate venture big enough?”.

Market Size in the Context of New Corporate Ventures

New ventures within a corporate are formed, explored, pitched and funded in a context that heavily influences how teams answer the question “is this new venture big enough?” and how executives decide whether it’s big enough.

Most of this comes back to the scale at which corporates are operating at.

Formation

When a large company is forming or looking to start a new venture, it often comes at it from a problem or opportunity identified through an existing line. These existing lines of business, especially in larger companies, usually have revenues in the tens of millions, hundreds of millions and often billions.

The problem pursued is often a problem experienced by the business in acquiring customers, retaining customers or growing customer lifetime value.

“We’re growing at 5%, but I’ve been asked to get to 7% to increase profits to $300m, so I need to acquire customers faster. Let’s set up a new venture that will increase my ability to acquire by 2%.”

The way to address the problem or pursue the opportunity is then informed by market trends and aggregated feedback. “Well, 20% of our new customers say that they’re really into sustainable energy, so how can we use this trend?”

Due to the sheer scale required, a new constraint is introduced to the still unformed venture of “it must apply to all our customers so that it can move the needle”. Going back to the example we’re working through, a smaller segment of the company’s high-income customers isn’t palatable because it may only get 0.5% growth for the corporate that is only tens of millions.

None of the above is inherently wrong or bad. It just needs to be understood for what it is, the business driving the formation of the new venture top down, not the customer. In non-venture land, it makes complete sense to form new initiatives from this perspective. You need to think and operate at scale.

Before you say “but we used customer feedback” my counter is, the feedback is biased (by your offer and the scale makes it a challenge).

The other method of forming a new idea for a venture in a large company is to compile a long list of possible opportunities. There is a subset of opportunities that commonly result from this listing method of forming new venture ideas, that come from market trends or market sizes. Trends and markets that are deemed too small are culled. So you’re left with opportunities that are big enough to be considered as attractive to the corporate.

On the one hand, this allows the company to quickly focus on large, exciting opportunities in a macro sense that have the potential to materially impact the business financially.

On the other hand, it introduces two problems before exploration has even begun on the new venture. First, many disruptive businesses start in markets that haven’t yet emerged as large enough to “move the needle” on a large corporation. Second, if you start with “artificial intelligence will be a $20bn+ market, let’s go into AI” you’ll have trouble making the viable opportunity you find in this market look big enough in relative terms.

Exploration

Once the idea is formed and approved for exploration, teams – more often than not – set to work exploring a venture to solve the problem the business had. Looking for ways to solve that acquisition issue rather than thinking about what really matters for the customer.

It also often leads to an understanding of the customer that is lopsided. This comes about because the customer is analysed, interviewed and researched in relation to the macro problem or opportunity the business has, rather than to what the customer cares of. This can lead to false validation.

For example, a team might explore a customer need in the domain of solar (because renewables are a key trend) to which the customer responds favourably. The team’s also able to bring in compelling, broad-brush survey results on what people think about solar. However, what this might miss (and usually does miss) is that solar isn’t as important as other things in the customer’s life. So, if an offering were put together, customers wouldn’t take it up despite having such good feedback during exploration.

Don’t get caught up on solar itself. I’m not trying to make an assessment of renewables or solar. I’m just using it to illustrate my point.

In the same way technologists and engineers are infamous for building solutions, then looking for problems, corporate venture folks (me included) are guilty of taking a business problem and looking for a customer problem it solves. It needs to be the other way around.

The “is it big enough question” is easier to answer with the trends and broad market appeal. But in searching for this broad market appeal and solving the large scale business problem the customer is often lost sight of or early validation is discounted (“but that’s only a 20 interviews and 200 landing page clicks, how do we know it will scale to 1,000,000 customers?”).

Furthermore, teams can begin to learn that this gets a negative response, so they stray towards more fluffy language and broader trends (“data ecosystem” anyone?).

Pitching

“Be ambitious, ACMECo has tonnes of cash” – actual advice.

“The CEO is used to seeing plans for $100m, increase the pitch from $1m to $10m. $10m will seem more important and like we know what we’re doing so she’ll say yes.” – also actual advice.

Before you think I’m taking the high horse, I’ve been guilty of this type of advice and thinking.

The quotes I’ve shared start to give you a sense of how the pitch itself starts to influence the “is this big enough” question itself. At this stage of the process, teams want their idea to get up and be funded. A few factors start to come into play.

Some teams get nervous. They’re about to present to their superiors and sometimes executives multiple levels away. They don’t want to fail, and they also don’t want to be seen as someone small minded pursuing a small idea. So they start to second guess themselves and begin modifying the pitch to be bigger and smarter.

Other teams are ambitious to replicate the best of Silicon Valley (admirably). After 12 weeks of an “innovation sprint”, they’re pitching like they’re a Series B venture in San Francisco with six years of proven traction under their belt.

Other teams start thinking about the optics. The quote I shared earlier captures this well. Teams want their idea to register with the executive team. They want this initiative to be Strategic and Important (capital S and I is key). So they look for ways to inflate it.

Of course, you can stick to your guns. Confidence also wins pitches – even if you don’t seem as ambitious as the others.

Deciding to Fund

The executives themselves now have to consider whether they’re going to fund this new venture. One of the key questions they will ask is, “is this venture big enough?”

Anecdote: I once worked with a listed board that said Afterpay wasn’t big enough to pay attention to. Afterpay passed them in market cap a while ago.

When looking at this, the executives will have in their minds their company’s revenue and profit. If their company is doing $1bn in revenue, then they’ll be thinking what chance the venture has in impacting this meaning your idea had better show millions. This is an understandable frame to come from, and it might be the most appropriate with some new ventures. That doesn’t mean it’s always the right frame or the only frame.

Anecdote: Atlassian’s Jira Service Desk started as a hack day project and went out to a few customers. It solved problems. No one asked “is this big enough” in the early days. Now it’s a huge part of Atlassian’s revenue.

Executives involved will also be considering the ambition factor. If they get behind this, does it show their ambition? Will it bring kudos and media attention?

I’ve observed that when teams clearly articulate the customer problem and put forward a good solution to it, the language becomes free of corporate buzzwords. This makes it feel less ambitious on the surface because of its simplicity, especially to a time-poor executive. Meaning it won’t feel big enough.

Market Size in the Context of Startup Ventures

The context of new startups is reasonable well covered elsewhere so to unpack the “is the venture big enough question”, we’re just going to focus on a few key topics with new ventures:

- A startup is a search for a business model, and a key part of the search is solving a customer problem (Steve Blank).

- Do things that don’t scale (Paul Graham, founder Y-Combinator): provide a few relevant insights:

- The question to ask about an early-stage startup is not “is this company taking over the world?” but “how big could this company get if the founders did the right things?”

- Sometimes the right unscalable trick is to focus on a deliberately narrow market. That’s what Facebook did.

- There are many examples of non-scalable activities that enabled scalability later.

- The only thing that matters is product/market fit (Marc Andressen).

- The market is the most crucial factor in a startup’s success or failure.

- In a terrible market, you’ll break your pick for years trying to find customers who don’t exist for your marvellous product.

- When you are [before product/market fit] focus obsessively on getting to product/market fit.

- Startups fail because they never get to product/market fit.

- Y-Combinator’s Guide to Seed Funding says include “the (huge) Market you are addressing – Total Available Market (TAM) >$1B if possible. Include the most persuasive evidence you have that this is real.”

- Tackle a small market (Sequoia) where you can start without being crushed. This will position you so you can expand to broader markets.

Market Size Over the Early Venture Lifecycle

There is some more context that helps consider the question of “is the venture big enough?”, the lifecycle of the venture itself and where you are in it.

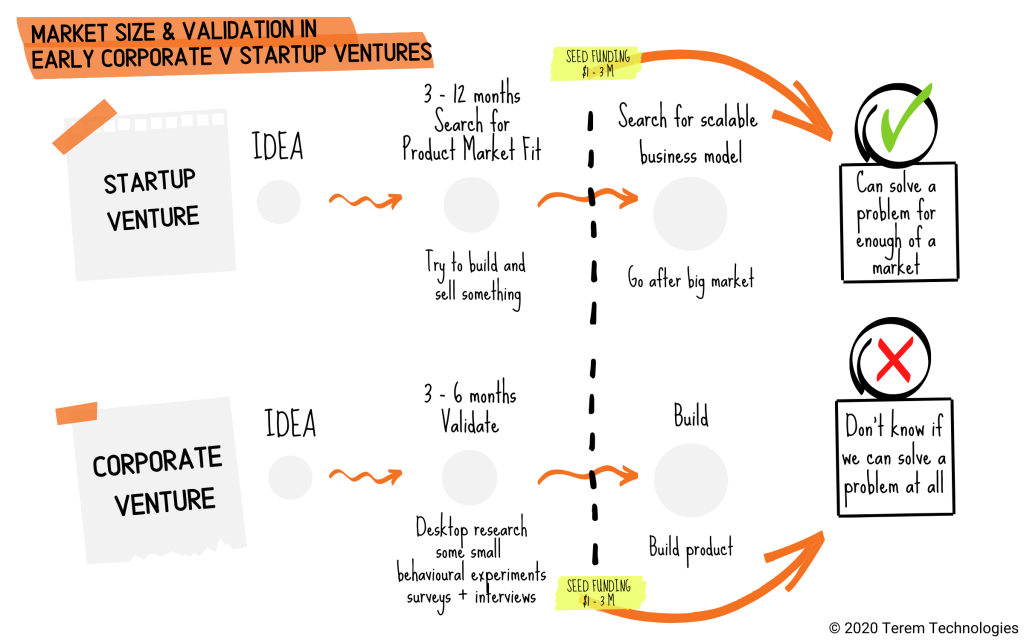

Generally speaking, there is usually some misalignment between corporate venture funding milestones and process with startup venture funding milestones and maturity. Corporates seed fund an idea sooner than today’s startups see funding. Today’s startups generally have put in significantly more work and shown more traction at seed than corporate ventures.

You can get a sense of the differences in the sketch below:

New corporate ventures are usually seeking and obtaining Seed Funding ($1-3m) earlier in maturity than startups seek and obtain an equivalent amount of funding. An internal corporate venture will usually have performed desktop research, interviewed customers, run surveys and (if they’re good) performed some behavioural experiments. Startups, on the other hand, have likely been selling (or trying to sell) their product to real customers and users (they have to or they don’t get paid).

At the same funding gate, the startup has a clearer view of who the customer is and what the market is. It’s also clearer, in relative terms, about whether the startup has a pathway to the larger market. The corporate venture has a hypothesis about the customer, the first market – their beachhead – and then the bigger market. And, if the corporate venture has really worked on their customer value proposition and viability well, the first market will be narrow.

Comparing the lifecycles of new corporate ventures and startups in their early stages ultimately illustrates the awareness that we need to have in corporate venture land when looking at the market size for the venture. We likely aren’t going to have the same level of validation that a startup receiving a similar amount of funding will.

In practice, this lower level of validation makes it harder to draw pathways to Being Big Enough and harder to believe pathways to Being Big Enough. It means we need to think a bit more deeply about the market the venture is initially going after and where it could get to.

Questioning “Is The Venture Big Enough?”

Some questions we can ask to get a better answer to “is the venture big enough?”

- How big could it get if we get it right?

- Is the beachhead sustainable enough to give us a platform to go bigger?

- Do we see plausible options to go bigger?

- How strong is the immediate customer problem that we will solve? How likely is it we’ll have product/market fit within 12 months in our initial market?

I want to emphasise how important it is to shift executive stakeholders from the zone they are used to – the zone of sequential business planning at a macro scale – to the micro-scale that matters in new ventures. Will we solve a genuine customer problem that matters to enough people to start with?

Final Remarks

This was primarily a way of working through a topic that has been playing on my mind for the last year, or so. I’ve tried to avoid the judgement of the way corporates or startups go about venturing. I’ve tried to mainly focus on unpacking the context in this post because it will help me (and hopefully someone else) reason about market size in the venture(s) they’re working on and communicate more effectively with others involved in the venture on the topic of market size.

Scott Middleton

CEO & Founder

Scott has been involved in the launch and growth of 61+ products and has published over 120 articles and videos that have been viewed over 120,000 times. Terem’s product development and strategy arm, builds and takes clients tech products to market, while the joint venture arm focuses on building tech spinouts in partnership with market leaders.

Twitter: @scottmiddleton

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/scottmiddleton