When a cycle of Product Discovery is finishing you will be often faced with a decision point. The knowledge you and your team gained during Discovery has likely cast doubt on your initial assumptions, uncovered new opportunities and changed the shape of your plans. With Discovery ending, you will need to decide what to do next, and it will likely differ from what you thought you would be doing. It isn’t usually an easy decision either.

You, your team or those around you will have built momentum and belief in the idea you started with, a problem, a product, maybe even a whole new business. You must have had some level of commitment; otherwise, you wouldn’t have undertaken Discovery activities.

It’s this momentum and commitment that makes the end of Discovery decision harder. Inertia may lead you to continue down the path you started on, and you may need to fight this.

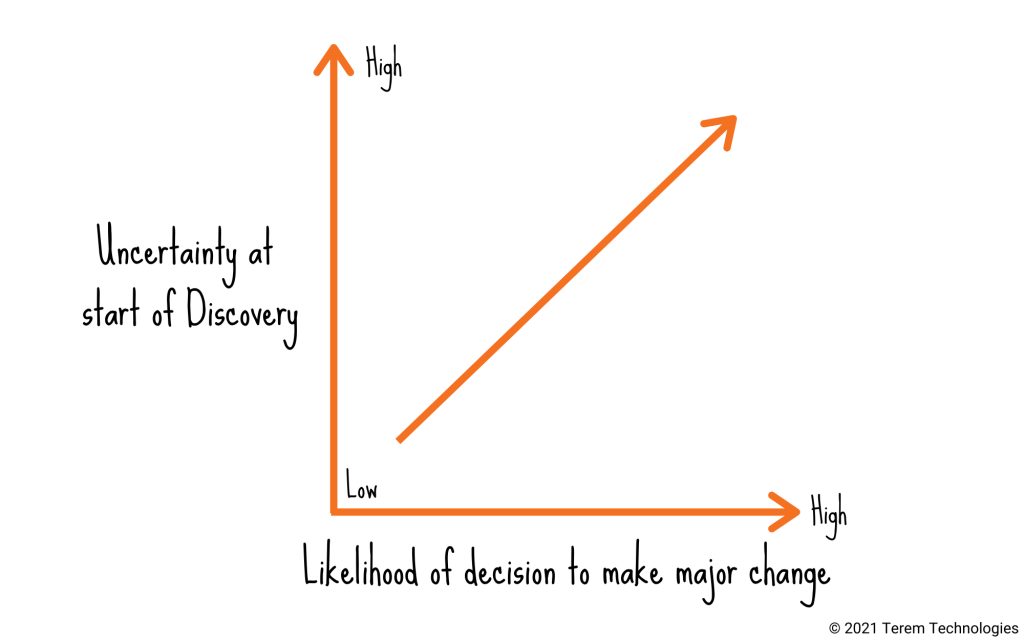

A Discovery will uncover new information. The more uncertainty there was at the start of Discovery, the more information you’re likely to uncover. Additionally, the more uncertainty, the more likely you will need to make a major decision to change your planned product.

This is exactly what Discovery is great for; uncovering new information to help you understand and design a better product and, ultimately, business.

It’s the decision near the end of a Discovery cycle where I see it gets tricky. It gets tricky because there are people involved, and there is a decision to be made (usually). It’s tricky because the decision is what sets you up for success (or failure).

The purpose of this article is to make this decision less tricky by providing a frame of reference to make better decisions near the end of Product Discovery. This article focuses on decisions in the context of a new product, a new venture, and a major new feature or release. This is where the impact and difficulty of reaching a decision are highest. However, it could be applied to more incremental decisions.

What we’ll cover:

- Types of Decisions

- Techniques for Making a Decision

- Writing a Decision Memo

1. Types of Decisions

At the end of a Discovery cycle, you actually only have a limited set of options to choose from about the types of decisions you can make:

- Proceed with the initial idea as-is: you continue with what you were planning at the start of Discovery with minimal changes.

- Proceed with modifications: you continue with what you were planning but with some modifications to it.

- Pivot: you change direction based on the results of your Discovery activities, focusing on a different idea, problem or product.

- Kill: you decide not to pursue this avenue or the avenues your Discovery activities revealed any further.

- Defer: you decide not to put any further effort into this idea or the ideas that came out of Discovery for now, with a plan to return to it at a later date.

With these types of decisions in mind, you can start to put the specifics for your team into them. There are some general rules of thumb that you can take with each type of decision, as well as follow some general ramifications. Here they are:

- In new ventures or significant new products proceeding with the initial idea as-is is, after being involved in many Discoveries, the most unlikely path that will eventuate. It is almost impossible not to learn something that will substantially modify your idea, cause a pivot or kill it when you’re dealing with very new initiatives.

- Undertaking a pivot will involve, in some ways, re-evaluating more than just the problem or idea but most likely the business model. This is often a significant challenge for established businesses and startups, so they have a tendency to force insights taken from Discovery into the mould of their business model.

- Kill is the hardest decision to take, but isn’t taken enough.

- When making a Defer decision, just question whether it’s a kill, but you don’t have the heart.

- If you don’t like the results of a Discovery, you can redo it.

It’s worth walking through the types of decisions a Discovery may lead to at the outset with your key stakeholders to get them comfortable with the decision they may need to make (e.g., killing an idea).

2.Techniques for Making a Decision

When it comes to making the decision itself, there are some techniques that you can use to help. Decision making is both an art and science with a significant body of knowledge that we won’t be able to do justice to here. However, in order to arm you with some techniques that you can apply immediately, here are some tools to use:

- Argument Mapping: this is where you use a visual tool to represent the logic you are using to make a decision. It will help uncover assumptions and flaws in logic. It will also more easily help you share your reasoning with your team.

- 4 Questions to ask with a new product or venture: Do we want to be in this space? Is this a good enough idea in the space? What’s the single biggest assumption that needs to be validated right now? Can we afford to bet on validating this assumption?

- Setting product success metrics: see if you’re able to set achievable metrics for success for each of the options in front of you. Are they valuable to your business and your customer?

- Writing a Discovery Decision Memo: see below.

- Address the organisation’s need for certainty when there is only uncertainty. Established organisations struggle with uncertainty. Confront this head-on and be aware of it.

For those that want to really dig into decision-making, pick up books like Thinking, Fast and Slow, and Fooled by Randomness.

3. Writing a Discovery Decision Memo

The final step for a major cycle of Discovery needs to be a written memo, either a document or slide, that outlines the decision you are making and why.

The investment memo is a tool commonly used by venture capitalists, angel investors, private equity firms and other investors to explain why they are investing in a company. It’s perfect for product decisions at the end of Discovery because these are investments just made by your company rather than an investor.

An investment memo is a clear and concise articulation of the key components of your company and what the rationale is for investing in it.

Y-Combinator

Here are some of the sections you might want to include in your memo:

- Summary: summarise the findings from Discovery, options, best path and next steps.

- Insights: share the key insights learnt through Discovery.

- Risks: outline the risks you’ve considered and how you will address them (or not).

- Market: discuss the competitive landscape and total opportunity size for the new product, venture or feature.

- Team & Capability: do you have the right team and the right capabilities to execute on this?

- Next Steps: share the product vision, roadmap for the next steps, and the criteria you will measure failure or success against.

That being said, clear reasoning over a few paragraphs without any headings in an email is perfectly fine. Just get something down on paper.

I, personally, prefer the written format over slides or visuals because writing forces strong logic.

Read more:

Scott Middleton

CEO & Founder

Scott has been involved in the launch and growth of 61+ products and has published over 120 articles and videos that have been viewed over 120,000 times. Terem’s product development and strategy arm, builds and takes clients tech products to market, while the joint venture arm focuses on building tech spinouts in partnership with market leaders.

Twitter: @scottmiddleton

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/scottmiddleton